Classical Mechanics – Newtonian Mechanics: “How an Apple Changed the World” (60 minutes)

The Foucault pendulum is one of the most impressive experiments in the history of physics, as it provides a tangible demonstration of the Earth’s rotation. The experiment, first conducted by the French physicist Léon Foucault in 1851, does not require complex setups or expensive equipment but is based on simple physical principles that can be observed by everyone.

In 1851, Foucault had the idea to use a pendulum to prove the Earth’s rotation. The pendulum he used consisted of a heavy mass, typically a metal sphere, suspended from a long wire. In his first demonstration, Foucault used a pendulum approximately 67 metres long with a mass of about 28 kilograms, which was installed in the dome of the Panthéon in Paris.

When the pendulum starts to swing, its trajectory initially remains fixed relative to the stars (in an inertial reference frame). However, as the Earth rotates beneath the pendulum, its trajectory appears to shift relative to the ground. In reality, the pendulum maintains the same direction, but the Earth’s rotation causes this apparent change. The Earth’s rotation becomes easily perceptible through the movement of the surface beneath the pendulum (as shown in the image).

Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton – Ideas and Experimental Study

Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) – Ideas and Experimental Study

According to tradition, Galileo studied the motion of many different objects with the aim of observing the rate at which they fall. In particular, by dropping objects from the top of the Leaning Tower of Pisa, he studied their motion and concluded that the acceleration of a falling object is independent of its weight.

Isaac Newton (1642–1727)

The English physicist Isaac Newton, who is considered the father of Classical Physics, built upon Galileo’s observations, Kepler’s laws of planetary motion, and the observation of an apple falling from a tree to formulate the three laws of motion and the famous law of universal gravitation.

Translational, Rotational, and Combined Motion

A rigid body can undergo translational, rotational, and combined motion.

In translational motion, all points of the body have the same velocity at every moment. An example of this is the motion of a box sliding on a horizontal surface.

The laws governing the motion of rigid bodies in translation are the same as those that apply to the motion of material points.

Periodic Motion and Hooke’s Law

Periodic Motion or Oscillation

Periodic motion or oscillation is a type of motion that repeats itself at regular time intervals. It occurs when a body is in a position of stable equilibrium and experiences a restoring force whenever it is displaced from that equilibrium position.

Hooke’s Law

A simple system of periodic motion is a stretched spring. To keep the spring extended by an additional length x beyond its original length, a force F must be applied at each end. In 1678, Robert Hooke formulated Hooke’s Law, which states: “The extension is proportional to the force, provided the extension is not too large.”

Exhibit:

“Ball Recycling”

In this exhibit there is a ball “recycling” system. The ball is placed at the top end of the system and we observe how it travels all the way to the other end. More specifically, the forces of gravity and the vertical force are exerted on the body, while their resultant centripetal force is what keeps the sphere within the circular orbit.

Exhibit:

In this exhibit, there is a system of ball movement as a combination of horizontal and vertical movement. We observe that by successively placing the balls at the top of the system, the balls end up at the same point regardless of their mass. This happens because the trajectories that bodies travel and, by extension, the range they reach do not depend on the mass of the body in question.

Electromagnetism: Taming the Lightning (60 minutes)

The chaotic pendulum is an example of a mechanical system that exhibits chaotic behavior under specific conditions. It is characterized by sensitivity to initial conditions, meaning that even small differences in initial conditions can lead to drastically different future behaviors of the system.

The chaotic pendulum system typically consists of a simple pendulum oscillating around a fixed point, with the addition of external forces such as friction or a periodic external force. Instead of following a predictable, periodic trajectory, the chaotic pendulum can exhibit non periodic, complex trajectories that never repeat exactly in the same way (a fundamental observation). This type of behavior is one of the typical examples of what can happen in dynamical systems governed by nonlinear equations of motion. The chaotic pendulum is often used to study the principles of chaos and nonlinear dynamics.

Chaotic oscillatory motions influenced by magnets are an interesting phenomenon frequently studied in physical systems where the motion of an object, such as a pendulum, is affected by magnetic fields. These systems can exhibit extremely complex and unpredictable movements due to the interaction between magnetic forces and restoring forces.

John Scott Russell and the Discovery of Solitons

John Scott Russell was a Scottish engineer and physicist who lived during the 19th century. Although he was already renowned for his work in shipbuilding and structural engineering, Russell became best known for discovering a unique phenomenon during his experiments with water waves.

In 1834, while conducting research on the propulsion of boats in a canal in Scotland, Russell observed something extraordinary. A wave generated by the sudden stop of a boat continued to travel along the canal without changing its shape or speed for a long distance. This was the first recorded observation of a ‘solitary wave,’ which maintained its energy and uniformity as it moved forward.

The discovery of solitons has influenced many fields in physics and applied mathematical analysis. Today, solitons are used to describe phenomena in various domains:

– Optical Fibers: In optical fibers, solitons can be used to transmit data over long distances without loss, as they preserve their energy.

– Plasma Physics: Solitons play a significant role in studying wave-particle behavior in plasmas.

– Field Theory and Particle Physics: Solitons appear as solutions to various nonlinear field theories and are associated with stable particle-like states.

John Scott Russell’s discovery of solitary waves laid the foundation for a new class of physical phenomena—solitons—which remain among the most fascinating and significant subjects of study in modern physics and mathematics. Their ability to retain their integrity through interactions and to move without energy loss makes them valuable in many technological applications and scientific investigations.

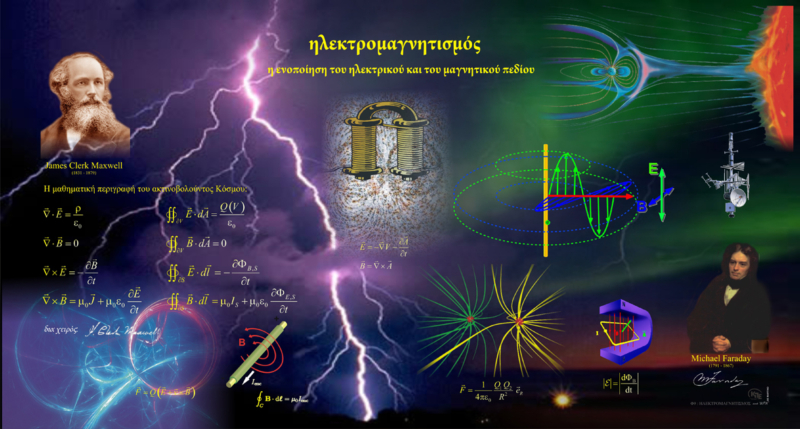

Fundamental Understanding and Applications of Electromagnetism

The unification of the electric and magnetic fields is central to understanding electromagnetism, as described by Maxwell’s equations. Developed by James Clerk Maxwell in the 19th century, these equations combine the theories of electric and magnetic fields into a unified theory that is fundamental to both physics and technology.

Maxwell’s Equations

Maxwell’s equations describe how electric and magnetic fields interact and propagate through space:

- Gauss’s Law for the electric field: ∇⋅E = ρ/ε₀

This states that the electric field E is generated by electric charges (ρ). The field’s intensity is directly related to the distribution of charge. - Gauss’s Law for the magnetic field: ∇⋅B = 0

This means that magnetic fields have no sources or sinks—there are no isolated magnetic charges. Magnetic field lines form closed loops. - Faraday’s Law of Induction: ∇×E = −∂B/∂t

An electric field is generated by a changing magnetic field over time. - Ampère-Maxwell Law: ∇×B = μ₀J + μ₀ε₀∂E/∂t

A magnetic field is generated by electric currents (J) and by a changing electric field over time.

Electromagnetic Waves

Maxwell’s equations show that electric and magnetic fields can generate waves that propagate through a vacuum as electromagnetic waves. These include radio waves, microwaves, infrared rays, visible light, ultraviolet rays, X-rays, and gamma rays. These waves travel at the speed of light and require no material medium for propagation.

Relativity and Unification

Albert Einstein’s special theory of relativity in 1905 expanded our understanding of the unification of electric and magnetic fields. It shows that electric and magnetic interactions depend on the observer’s frame of reference. According to this theory, electric and magnetic fields are not fixed but transform based on the motion of the observer, confirming that electric and magnetic forces are two aspects of the same phenomenon and can be viewed as a single electromagnetic field.

Modern Perspective

The unification of electric and magnetic fields is crucial to our understanding of the fundamental forces of nature and has influenced technological advances such as radio communication, electronics, and optical spectrum applications. Modern physics continues to examine this unification through quantum electrodynamics (QED) and the ongoing search for a unified theory combining all fundamental forces.

This unified understanding has opened new research and technological frontiers, allowing the development of advanced applications and deepening our comprehension of the universe.

Historical Overview of Electricity, Magnetism, and Their Unification

- Early Observations and Development

– Ancient Greece (6th century BCE): The first observations of electricity came from Greek philosophers such as Thales of Miletus, who noticed that amber (electron) could attract light objects when rubbed.

– Ancient Chinese and Indians: Both civilizations observed electromagnetic phenomena, such as the Chinese use of voltaic elements for medicinal purposes.

- Discoveries in Electricity and Magnetism

17th Century:

– William Gilbert (1600): In his work ‘De Magnete,’ Gilbert separated the study of magnetism from electricity and described the magnet as a source of the magnetic field, not a result of electric charges.

18th Century:

– Benjamin Franklin (1752): Conducted experiments with electricity and introduced the concepts of positive and negative charge. His famous kite experiment is widely known.

– Charles-Augustin de Coulomb (1785): Presented Coulomb’s Law, describing the interaction between two electric charges.

- 19th Century Discoveries and Theories

– 1820:

Hans Christian Ørsted: discovered that electric current can generate a magnetic field, reinforcing the connection between electricity and magnetism.

– 1821:

Michael Faraday: conducted experiments leading to the discovery of electromagnetic induction, theorizing that changes in magnetic fields generate electric currents.

– 1831:

Faraday: introduced the concept of the electromagnetic field, forming the basis for the theory of electromagnetic waves.

– 1845:

James Clerk Maxwell: formulated the equations combining all known theories of electricity and magnetism, showing that the electric and magnetic fields are interrelated and depend on the movement of electric charges.

- Special Relativity and the Expansion of Electromagnetism

– 1905:

Albert Einstein: special relativity further demonstrated the dependence of electric and magnetic interactions on the observer’s frame of reference.

– 1915:

Einstein: general relativity broadened the understanding of gravity in combination with other forces, paving the way for the concept of a unified theory encompassing all fundamental forces.

- Modern Developments and Unification

– 20th Century to Present:

Quantum Electrodynamics (QED): QED, developed by Richard Feynman, Julian Schwinger, and Tomonaga Shinichiro, provides a complete description of electromagnetic interactions at the quantum level.

– Supersymmetry and Grand Unified Theories: Modern physicists continue to search for unified theories that combine all fundamental forces, including String Theory and Grand Unification.

Conclusion

The unification of the electric and magnetic fields has advanced significantly from ancient observations to modern theories that shape our understanding of physics and technology. Maxwell’s theories and subsequent discoveries continue to form the foundation of contemporary physics and technology, revealing the profound connection between the fundamental forces of the universe.

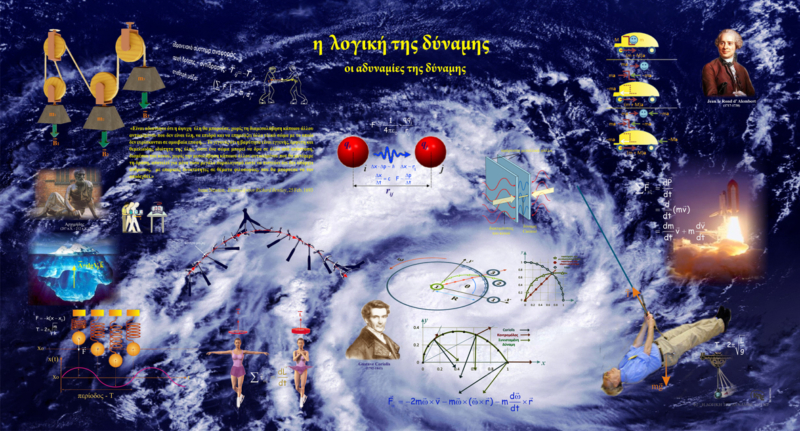

The concept of interaction and energy is fundamental to understanding physical phenomena. Let’s look at these two elements in detail:

Interaction

Interaction refers to the forces exerted between two or more objects or particles. The fundamental types of interactions in physics are:

- Gravitational Interaction: The force that attracts all bodies due to their mass. It is the force that keeps planets in orbit around the Sun.

- Electromagnetic Interaction: Acts between charged particles. It is responsible for electric and magnetic phenomena and chemical bonding between atoms.

- Weak Nuclear Interaction: Responsible for radioactive decay and certain nuclear reactions.

- Strong Nuclear Interaction: The force that holds protons and neutrons together in the nucleus.

Energy

Energy is a fundamental property of systems, transferable or transformable between different forms:

- Kinetic Energy: The energy an object has due to its motion, Eₖ = ½mv², where m is the mass and v is the velocity of the object.

- Potential Energy: The energy of position in a force field such as gravity or electromagnetism.

- Thermal Energy: Associated with random motion of particles in matter. It is the energy that causes a body to heat up.

- Chemical Energy: Stored in chemical bonds and released in reactions.

- Nuclear Energy: Stored in atomic nuclei, released during nuclear reactions.

Interaction and Energy

Interactions often lead to energy exchange:

– In collisions, kinetic energy transfers between objects.

– When lifting an object, kinetic energy transforms into potential energy.

– In chemical reactions, chemical energy transforms into thermal or other forms of energy.

According to the law of energy conservation, energy is never lost but changes form through interactions.

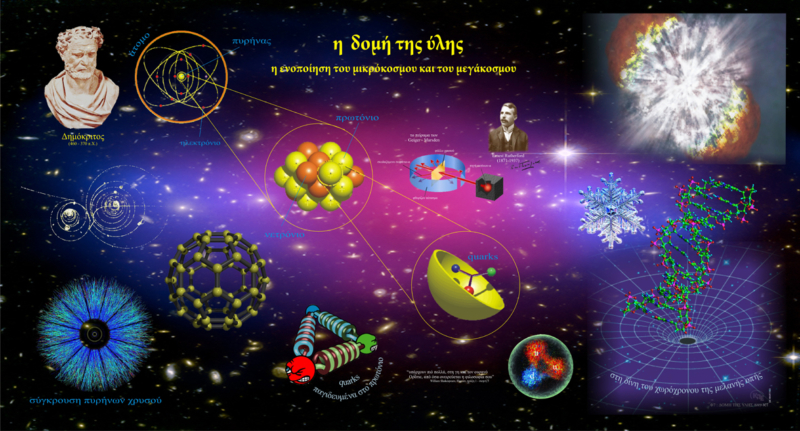

Interactions in the microcosm, that is, at the subatomic level, are governed by four fundamental forces or interactions. These forces are responsible for the behavior of particles and the formation of matter as we know it. Let’s look at these four interactions in detail:

- Strong Nuclear Force: The strongest, operating at ~10⁻¹⁵ m; mediated by gluons.

- Weak Nuclear Force: Responsible for β-decay; mediated by W⁺, W⁻, and Z⁰ bosons.

- Electromagnetic Force: Acts between charged particles; mediated by photons.

- Gravitational Force: The weakest but acts at all distances; possibly mediated by gravitons.

Interactions and Field Theory

In the microcosm, these interactions are described through Quantum Field Theory, where particles are considered excitations of quantum fields. Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD) describes the strong force, while Electroweak Theory describes the unified description of the electromagnetic and weak forces. These interactions in the microcosm are fundamental to understanding the nature of matter and the forces that shape it, playing a crucial role in the processes that determine the existence of the universe. The interactions that take place in radioactive materials are mainly associated with radioactive decay, which is a process in which unstable atomic nuclei emit energy in the form of radiation. This decay can occur through various mechanisms, each of which is associated with specific types of radiation and interactions. The main types of radioactive decay are:

- Alpha Decay: Emission of a helium nucleus (2 protons, 2 neutrons); reduces atomic number by 2.

- Beta Decay: Conversion between neutron and proton:

* Beta-minus (β⁻): Neutron → proton + electron + antineutrino.

* Beta-plus (β⁺): Proton → neutron + positron + neutrino.

– Gamma Radiation: High-energy photons emitted as the nucleus transitions to a lower energy state.

– Neutron Emission: Some isotopes emit free neutrons during decay.

Interaction of Radiation with Matter

Radiation from radioactive materials interacts with matter by:

– Ionization: Ejecting electrons from atoms, creating ions—potentially damaging to living cells.

– Excitation: Raising electrons to higher energy levels; upon return, light is emitted.

– Compton Effect: Gamma photon scatters off an electron, reducing its energy.

Photoelectric Effect: When a photon strikes a bound electron, it can impart all of its energy to the electron and eject it from the atom, causing ionization.

Applications and Hazards

Radioactive materials are used in many fields, such as medicine (for diagnosis and treatment), industry (for quality control of materials) and energy (nuclear energy). However, the radiation they emit can be hazardous to health and careful control and protection are required during their use.

Understanding these interactions is essential for leveraging the benefits and managing the dangers of radioactivity.

Modern Physics: From infinity to infinity (90 minutes)

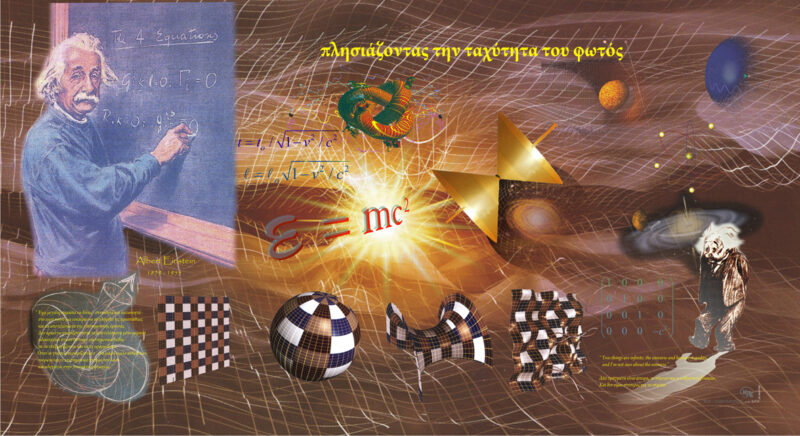

Postulates of the Special Theory of Relativity – Einstein (1905)

- The laws of nature are the same for all inertial reference frames. Any reference frame moving at a constant velocity relative to an inertial reference frame is also inertial.

- The speed of light is the same in all inertial reference frames.

Special Relativity

Each inertial reference frame follows the same laws of physics, and an observer within it can consider their own frame as “at rest.” Additionally, the speed of light remains constant across all inertial reference frames.

Motion is relative, as it is always defined in relation to a specific reference frame. This means that when an object moves, its position changes relative to something else.

Benham’s Disk Exhibit

The exhibit features Benham’s Disk, also known as “Benham’s Color Top.” This optical toy creates the illusion of colors when spun. It was invented by Charles Benham in 1894 and is used to study human color perception and the functioning of the visual system.

Basic Concepts: Heat, Thermal Radiation, and Energy Transfer

Black Body

In physics, a black body is defined as an idealized, perfectly absorbing surface that absorbs all incident electromagnetic radiation. It does not reflect, transmit, or scatter any radiation. The radiation emitted by a black body depends solely on its temperature. This theoretical model was introduced in 1860 by Gustav Robert Kirchhoff to study thermal radiation.

Heat

Heat is the form of energy transferred from one body to another due to a difference in temperature.

Thermal Equilibrium

When two bodies are in thermal contact, heat flows from the body at higher temperature to the one at lower temperature. Over time, their temperatures equalize and the heat transfer ceases. This state is called thermal equilibrium.

Mechanisms of Heat Transfer

Heat can be transferred through conduction, convection, and radiation:

– Conduction: The transfer of energy through a material without mass movement, based on molecular interactions. The rate of conduction depends on the temperature gradient and the cross-sectional area.

– Convection: The transfer of heat through the movement of masses from one region to another.

– Radiation: The transfer of energy via electromagnetic waves. The rate of radiative heat transfer depends on the temperature raised to the fourth power.

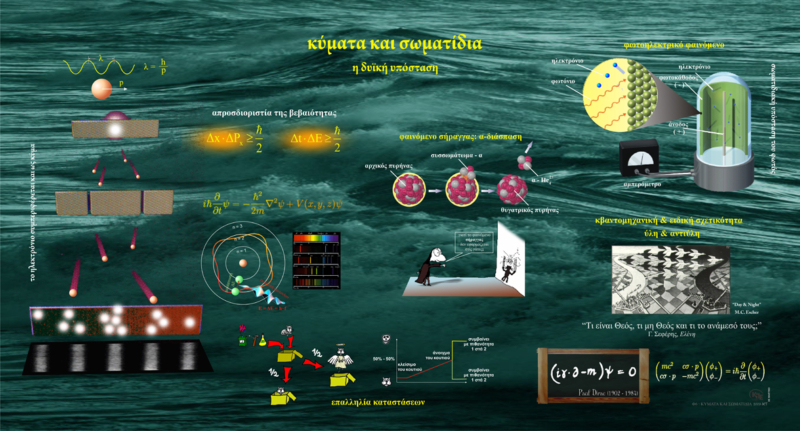

Analysis of the Dual Nature of Matter and Light and Standing Waves

The dual nature of matter and light, known as wave-particle duality, is a fundamental concept in quantum physics that describes how particles and radiation can exhibit both wave-like and particle-like behavior depending on the experimental conditions.

Wave Nature of Light and Matter:

The wave nature of light was first described by Christiaan Huygens in the 17th century. In 1801, Thomas Young’s double-slit experiment confirmed that light exhibits interference, a characteristic behavior of waves. In terms of matter, Louis de Broglie proposed in 1924 that particles such as electrons can also display wave-like behavior.

Particle Nature of Light and Matter:

The particle nature of light became evident through the photoelectric effect, studied by Albert Einstein in 1905. According to this phenomenon, when light strikes a metal surface, it ejects electrons from the metal. Einstein proposed that light consists of photons, which are quantized packets of energy.

Wave-Particle Duality:

Wave-particle duality explains the ability of particles and light to display either wave or particle properties depending on the experiment. This duality cannot be fully described by classical physics but is better explained by quantum mechanics.

Niels Bohr’s principle of complementarity emphasizes that wave and particle properties are complementary. Observing one excludes the simultaneous observation of the other. Thus, depending on the experiment, one can observe either wave or particle behavior, but not both at the same time.

Schrödinger’s Cat:

Schrödinger’s cat is a famous thought experiment proposed by Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger in 1935. It aims to highlight the paradoxes and strange implications of quantum mechanics when applied to macroscopic objects.

1D Standing Waves:

One-dimensional (1D) standing waves occur when two waves moving in opposite directions interfere along a line or medium, creating a pattern that appears stationary. These waves have nodes (points of no movement) and antinodes (points of maximum oscillation).

Creation and Applications:

These waves form in strings and tubes under specific boundary conditions. Applications include musical instruments, structural acoustics, and telecommunications.

2D Standing Waves:

Two-dimensional standing waves form on surfaces like membranes or plates. They exhibit patterns of nodes and antinodes in two dimensions. They are generated through vibrations in membranes (e.g., drum heads), Chladni plates, or water surfaces.

Applications include acoustics, quantum mechanics, structural engineering, and educational demonstrations.

Exhibits:

– Metal Plate: Demonstrates modes and eigenfrequencies via visible nodal patterns during oscillation.

– Tuning Fork: A sound device consisting of two U-shaped prongs mounted on a base, which resonates and produces fundamental and overtone frequencies upon excitation.

Unification of Electric and Magnetic Fields – Historical and Scientific Overview

Fundamental Understanding and Applications

The unification of the electric and magnetic fields is central to the understanding of electromagnetism, as described by Maxwell’s equations. Developed by James Clerk Maxwell in the 19th century, these equations combined the theories of electric and magnetic fields into a single unified theory, which holds fundamental importance for physics and technology.

Electromagnetic Waves

Maxwell’s equations demonstrate that electric and magnetic fields can generate waves that propagate through vacuum as electromagnetic waves. These include radio waves, microwaves, infrared rays, visible light, ultraviolet rays, X-rays, and gamma rays. These waves travel at the speed of light and do not require a material medium to propagate.

Relativity and Unification

Albert Einstein’s special theory of relativity in 1905 extended the understanding of the unification of electric and magnetic fields. It showed that electric and magnetic interactions depend on the observer’s frame of reference. According to this theory, the electric and magnetic fields are not fixed but transform depending on the motion of the observer. This discovery confirms that electric and magnetic forces are two aspects of the same phenomenon and can be considered as a single electromagnetic field.

Modern Perspective

The unification of electric and magnetic fields is crucial for understanding the fundamental forces in physics and has influenced technological advances such as radio communication, electronics, and optical applications. Modern physics continues to explore the unification of these forces through quantum electrodynamics (QED) and the pursuit of a unified theory that combines all fundamental forces of nature.

Historical Overview of Electricity, Magnetism, and Their Unification

In Ancient Greece (6th century BCE), early observations of electricity came from philosophers like Thales of Miletus, who noted that amber (electron) could attract light objects when rubbed. Chinese and Indian civilizations also observed electromagnetic phenomena and used voltaic cells for medicinal purposes.

Discoveries in Electricity and Magnetism

In the 17th century, William Gilbert (1600) in his work ‘De Magnete’ distinguished magnetism from electricity, describing magnets as sources of magnetic fields. In the 18th century, Benjamin Franklin (1752) conducted experiments on electricity, introducing the concept of positive and negative charges, including his famous kite experiment. Charles-Augustin de Coulomb (1785) formulated Coulomb’s law describing interactions between electric charges.

19th Century Discoveries and Theories

In 1820, Hans Christian Ørsted discovered that an electric current could generate a magnetic field, establishing a link between electricity and magnetism. In 1821, Michael Faraday conducted experiments leading to the discovery of electromagnetic induction. He proposed that changes in magnetic fields induce electric currents and introduced the theory of the electromagnetic field in 1831. In 1845, James Clerk Maxwell formulated equations integrating the known theories of electricity and magnetism, showing their interdependence through moving electric charges.

Relativity and the Extension of Electromagnetism

In 1905, Albert Einstein’s special relativity further extended the unification of electric and magnetic fields, demonstrating their dependence on the observer’s frame of reference. In 1915, his general relativity advanced the understanding of gravity in combination with other forces, laying the foundation for a unified theory of fundamental forces.

Modern Developments and Unification

In the 20th century and beyond, quantum electrodynamics (QED), developed by scientists such as Richard Feynman, Julian Schwinger, and Tomonaga Shinichiro, provided a complete quantum-level description of electromagnetic interactions. Theoretical frameworks like supersymmetry and string theory aim to unite all fundamental forces under one comprehensive theory.

Conclusions

The unification of electric and magnetic fields has evolved significantly from ancient observations to modern theories that shape our understanding of physics and technology. Maxwell’s equations and subsequent discoveries continue to underpin modern physics, revealing the deep connection between the fundamental forces of the universe.

Plasma Lamp

The plasma lamp is a decorative device based on the principle of plasma discharge. It operates by generating a high-voltage electric field inside a glass sphere filled with inert gases such as neon, argon, or a mixture of both. When high voltage is applied, the gas ionizes to form plasma. Plasma consists of positively charged ions and free electrons, creating characteristic glowing streams within the globe.

The photoelectric effect was first observed by Heinrich Hertz in 1887 during his experiments on radio waves. Hertz noticed that when light (or electromagnetic radiation) strikes a metallic surface, it causes the emission of electrons. However, this observation was not fully explained by the prevailing theories of light at the time, which were based solely on its wave nature.

In 1902, Philipp Lenard further investigated the phenomenon and discovered that the energy of the emitted electrons does not depend on the intensity of the light, but on its frequency. This contradicted the wave theory of light, which predicted that the energy of the electrons should increase with the intensity of light, regardless of its frequency.

A full explanation of the phenomenon was provided by Albert Einstein in 1905. Einstein proposed that light is not only a wave, but also a particle, consisting of energy quanta, which were later called photons. According to his theory, each photon has energy E = hν, where h is Planck’s constant and ν is the frequency of the radiation. When a photon strikes the surface of a metal and its energy exceeds the metal’s work function Φ (the energy required to release an electron from the metal), the photon transfers this energy to the electron, freeing it from the material.