«The triptych of geometry» (40 minutes)

The Pythagorean Theorem constitutes one of the most renowned theorems in the realm of athematics. According to Pythagoras’ theorem, within the framework of Euclidean Geometry, the squares of the sides of a right-angled triangle are related as follows: “the square of the hypotenuse of a right-angled triangle is equal to the sum of the squares of the two perpendicular sides.” The Pythagorean Theorem also holds in its converse form; that is, if the following relation among the sides of a triangle is satisfied, then the triangle is right-angled.

Although the theorem today bears the name of the Greek mathematician Pythagoras (570 BCE – 495 BCE), historical research suggests that it may have been formulated earlier as an empirical observation. The Pythagorean Theorem is notable for having received the greatest number of distinct proofs ever attributed to a mathematical theorem. Professor Elisha Scott Loomis (1852–1940), in his book The Pythagorean Proposition, compiled 367 different proofs, which are of historical, scientific, and pedagogical interest.

The Möbius strip is a remarkable object in the field of topology and mathematics, known for its unique properties. It is a nonorientable surface, meaning it has only one side and one edge.

How to Create a Möbius Strip

The Möbius strip can be easily constructed by:

- Taking a strip of paper.

- Giving it a half-twist.

- Joining the ends together to form a loop.

The result is a shape that defies intuition—a surface with no distinguishable “inside” or “outside”.

The Möbius Strip

The Möbius strip is a compelling object in the field of topology and mathematics, renowned for its distinctive properties. It is a non-orientable surface, meaning that it possesses only one side and one boundary. It can be readily constructed by taking a strip of paper, imparting a half-twist to it, and then joining its ends to form a loop. The result is the Möbius strip. The strip is named after the German mathematician and astronomer August Ferdinand Möbius, who discovered it independently of the German mathematician Johann Benedict Listing in 1858. It constitutes one of the earliest objects studied in topology, the branch of mathematics concerned with the properties of spaces that are preserved under continuous deformations.

History and Discovery

The Möbius strip is named after August Ferdinand Möbius, a German mathematician and astronomer, who discovered it independently in 1858. However, the concept was also studied by Johann Benedict Listing, another German mathematician, around the same time.

This shape became one of the first objects studied in topology, a mathematical field that examines properties of spaces that remain unchanged under continuous deformations (such as stretching or bending, but not tearing or cutting).

Mathematical Properties of the Möbius Strip

- One-sided surface: If you start drawing a line on the

Möbius strip, you will eventually return to your starting point without crossing an edge.

- Single edge: Unlike a normal loop or ring, which has two distinct edges, the Möbius strip has only one continuous boundary.

- Cutting Experiment: If you cut the Möbius strip along the center, it does not separate into two loops but forms one larger twisted loop.

Applications of the Möbius Strip

The Möbius strip has inspired many real-world applications in science, technology, and art:

- Engineering & Design: Used in conveyor belts to evenly distribute wear and tear.

- Mathematics & Physics: Studied in knot theory, topology, and electromagnetism.

- Art & Architecture: Inspires modern sculptures and structures.

- Biology: Appears in DNA structures and molecular formations.

Conclusion

The Möbius strip is a simple yet profoundly interesting mathematical object that challenges our understanding of space, dimensions, and orientation. Its unexpected properties make it a subject of fascination in both mathematics and real-world applications, continuing to intrigue scientists, engineers, and artists alike.

Euclid’s Elements is one of the most influential and iconic works in the history of mathematics and science. Written around 300 BCE in Alexandria, this work systematically organizes geometric knowledge into a coherent and logical framework, shaping mathematical thought and education for over two thousand years.

Structure of the Elements

The Elements consists of thirteen books, each addressing different aspects of geometry and mathematical theory. Euclid begins with basic definitions and fundamental axioms, gradually building towards complex theorems and proofs.

One of its defining characteristics is its rigorous logical structure.

- The theorems are derived step by step, using only previously proven propositions and fundamental axioms.

- This axiomatic method has become the standard in mathematics and sciences.

Axioms and Definitions

The work begins with definitions, axioms (postulates), and common notions, forming the foundation for all subsequent proofs.

- Definitions introduce fundamental geometric concepts such as points, lines, and planes.

- Axioms are self-evident truths that do not require proof.

- The most famous is the parallel postulate, which states that in a plane, two lines that do not intersect are parallel.

Theorems and Proofs

Building upon these axioms, Euclid proves various theorems using logical deduction.

- The Elements covers a range of topics:

- Plane Geometry (Books 1–6).

- Number Theory & Proportions (Books 7–10). o Solid Geometry (Books 11–13).

- Each theorem is carefully structured, ensuring a logical progression that reinforces fundamental principles.

Impact of Euclid’s Elements

For over two millennia, Euclid’s Elements served as the foundation of mathematical education.

- During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, it was translated into multiple languages and became the primary geometry textbook.

- The logical rigor and systematic approach made it a cornerstone of mathematical thought.

Beyond Mathematics

The axiomatic method introduced by Euclid influenced:

- Philosophy (logical reasoning and epistemology).

- Science (structured scientific inquiry).

- Engineering and architecture (practical applications of geometry).

Timeless Relevance of the Elements

Despite advances in modern mathematics, Euclid’s Elements remains essential.

- Mathematical proofs continue to follow the logical methodology set by Euclid.

- Students worldwide still study Euclidean geometry, reinforcing logical thinking and problem-solving

Conclusion

Euclid’s Elements is a masterpiece of structured knowledge, demonstrating how human reasoning can systematize concepts into a universal mathematical legacy. It remains a timeless reference, shaping the way we think, teach, and apply mathematics to this day.

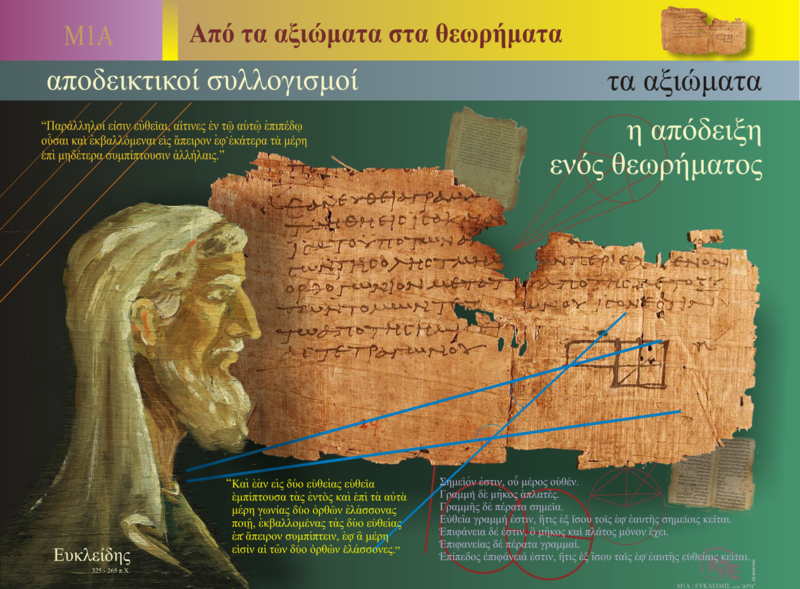

Euclid’s Elements

Euclid’s Elements constitute one of the most iconic and influential works in the history of mathematics—and indeed, of science more broadly. Written around 300 BCE in Alexandria, this work represents a systematic and methodical compilation of geometric knowledge, organized in a way that renders it accessible and logically coherent. Through a strictly logical approach, Euclid succeeded in organizing the pre-existing body of geometric knowledge into a unified, cohesive system, which served as the foundation of mathematical thought and education for over two thousand years.

The Elements consist of thirteen books, each addressing different aspects of geometry and other mathematical fields. Euclid begins with fundamental concepts and axioms and proceeds to develop more complex theories and propositions. The rigorous structure of the work is among its most defining features. The theorems are proven in a logical and systematic manner, relying upon the initial axioms and previously established propositions.

The treatise begins with a series of definitions, axioms, and common notions, which serve as the foundation for the development of the theorems. The definitions introduce the fundamental concepts of geometry, such as the point, the line, and the plane, while the axioms (or postulates) are propositions taken to be self-evident and requiring no proof. One of the most well-known of these is the fifth postulate, commonly referred to as the “parallel postulate,” which states that two lines in a plane that do not intersect are parallel.

Based on the axioms, Euclid proceeds to prove theorems—propositions that are demonstrated to be true through logical and mathematical reasoning. This method is known as the “axiomatic method,” and it became a fundamental practice in both mathematics and the physical sciences. Euclid was a pioneer in applying this method to the development of geometric theorems, and his work has served as a model for many subsequent scientific endeavors.

Each book of The Elements explores different dimensions of geometry. For example, the first six books are concerned with planar geometry, while the subsequent volumes extend to number theory, proportion, and solid geometry. The theorems within each book are structured such that each proof builds upon the previous ones, thereby creating a logical sequence that leads to a comprehensive understanding of geometric principles.

The Elements of Euclid exerted a profound influence on mathematical education and research for more than two millennia. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the work was translated into numerous languages and served as the primary textbook for the teaching of geometry. The logical rigor and clarity of its proofs made The Elements one of the most respected and studied texts in the history of mathematics.

Euclid’s emphasis on logic and systematic proof profoundly impacted other fields of knowledge, including philosophy and epistemology. His ideas regarding logic and the structure of knowledge were absorbed into the thought of philosophers and scientists, shaping the development of Western philosophy and science.

Despite the advancement of mathematics and the emergence of new disciplines, The Elements of Euclid remain both relevant and timeless. The methodology of rigorous proof introduced by Euclid continues to serve as a cornerstone of mathematical thinking and education. To this day, students continue to study Euclidean theorems as a fundamental component of their training in geometry, and the influence of his work remains vivid.

The enduring value of The Elements lies in their ability to provide a coherent and logically organized system of knowledge, which can serve as a foundation not only for understanding geometry but also for grasping the principles of logic and scientific methodology. Euclid’s work stands as a typical example of how human thought can systematize knowledge and create a lasting legacy that continues to shape education and science to this day.

Historical Context and Life of Pythagoras

Pythagoras was born on the island of Samos, located in the Aegean Sea, around 572 BCE. According to historical sources, he traveled extensively throughout his life, visiting Egypt and Babylon, where he came into contact with the philosophical and mathematical traditions of those civilizations. These experiences played a significant role in shaping his ideas and in the development of his teachings. Upon returning to Samos, Pythagoras founded his own school, which was soon relocated to Croton in Magna Graecia (modern-day southern Italy). The Pythagorean School was not merely a mathematical institute but a community that integrated philosophy, science, religion, and political thought. Members of the school adhered to a strict lifestyle, grounded in principles of discipline, simplicity, and communal living.

The Pythagoreans believed that numbers constituted the essence of reality. Arithmetic and geometry were not merely tools for solving problems, but expressions of the fundamental structure of the universe. Mathematical relationships and proportions were regarded as manifestations of the harmony and order governing nature. Central to Pythagorean doctrine was the concept of “perfect numbers” and “amicable numbers.” A perfect number is one that equals the sum of its proper divisors (excluding itself), such as the number 28 (1 + 2 + 4 + 7 + 14 = 28). Amicable numbers are a pair of numbers for which the sum of the proper divisors of one equals the other, such as the pair 220 and 284.

The Pythagorean Theorem is arguably the most well-known mathematical proposition associated with Pythagoras. Although this theorem was not developed exclusively by Pythagoras—since civilizations such as the Babylonians were aware of this property prior to his time—his formulation and logical proof marked a significant advancement in the systematic study of geometry. The Pythagorean Theorem states that in a right-angled triangle, the sum of the squares of the two legs (the sides forming the right angle) is equal to the square of the hypotenuse (the side opposite the right angle). This theorem is fundamental in numerous applications, including architecture, trigonometry, navigation, and other fields.

Pythagoras’s contributions extended beyond mathematics. His influence on music theory is equally significant. He discovered the mathematical ratios underlying musical harmonies, observing that the intervals between musical notes could be expressed as simple ratios of small whole numbers. This insight profoundly influenced music theory for centuries, and the connection between mathematics and music remains one of the most celebrated aspects of Pythagorean thought.

The Pythagorean School functioned not only as an academic community but also as a religious and philosophical brotherhood governed by strict rules. Its members lived communally, followed a strict diet (including vegetarianism), and devoted their time to study, meditation, and music. The Pythagoreans believed in the immortality of the soul and the doctrine of reincarnation. This belief deeply influenced their way of life and their worldview. Their teachings also had a mystical character, and knowledge was transmitted only to the initiated.

Pythagorean thought continued to exert significant influence after Pythagoras’s death. His ideas shaped the philosophy of Plato and Neoplatonism, as well as other philosophical and scientific traditions. During the Renaissance, Pythagorean ideas were revived and played an important role in the intellectual currents of the time, particularly in astronomy and music. Pythagoras’s legacy remains alive to this day. His ideas about the mathematical harmony of the universe continue to be studied and taught, and the Pythagorean Theorem remains a foundational principle in geometry. The Pythagorean vision of a cosmos structured by number, music, and order continues to inspire scientists, philosophers, and artists across the world.

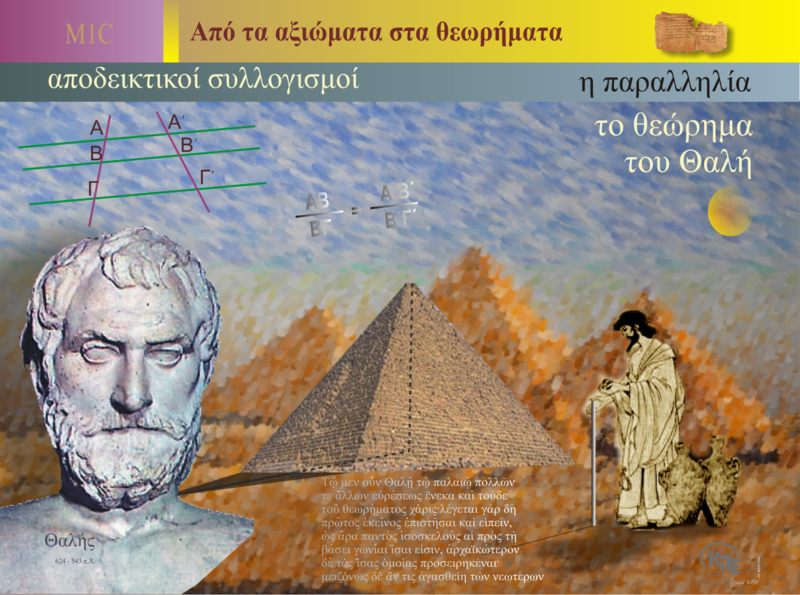

Thales of Miletus

Thales of Miletus, one of the Seven Sages of ancient Greece, was among the first to lay the foundations of Greek mathematical thought. He was born in Miletus around 624 BCE and is renowned for his contributions to mathematics, geometry, and astronomy. His work paved the way for the development of geometry and the philosophy of the natural sciences.

Thales is considered the father of Greek geometry. One of his most well-known contributions is Thales’ Theorem, which concerns the proportionality of the sides of two similar triangles. According to the theorem, if a straight line intersects two sides of a triangle and is parallel to the third side, then the two resulting triangles are similar, and their corresponding sides are proportional. This theorem forms one of the cornerstones of proportional reasoning in mathematics and is widely used in both geometry and trigonometry.

One of the most famous anecdotes about Thales involves his calculation of the height of the Great Pyramid of Giza. According to tradition, Thales used the lengths of shadows to determine the pyramid’s height. He calculated the ratio between his own height and the length of his shadow and applied the same ratio to the pyramid and its shadow. This method relies on geometric principles and the theory of proportions that he himself helped develop.

In addition to geometry, Thales also engaged in the study of astronomy. He famously predicted a solar eclipse in 585 BCE—an achievement regarded as a remarkable success at the time, enhancing his reputation as a wise man. Thales was also one of the first to propose that the Earth is a disc floating on water—an idea which, although simplistic by modern standards, represented an early attempt to understand the nature of the world through observation and reason rather than myth.

The concepts of parallelism and proportion are central to mathematics and were significantly developed by Thales. Parallelism—the property of two lines that do not intersect—is a foundational element in Euclidean geometry. Proportions, on the other hand, are essential for understanding relationships between different quantities and are widely used in solving geometric problems.

Thales laid the groundwork for the mathematical and philosophical developments that followed in ancient Greece. His influence was profound on later mathematicians such as Pythagoras and Euclid, and his approach to understanding the world through logic and observation remains a cornerstone of modern science.

The legacy of Thales—through his theorems, the principles of geometry, and his philosophical insights—continues to be taught and recognized as a foundational element in the history of mathematics and science.

«On the edge of infinity» (40 minutes)

Archimedes was one of the most influential mathematicians of antiquity, and his contributions to the calculation of areas and volumes laid the foundations for later integral calculus. The way he approached these problems was groundbreaking for his time and deeply influenced the development of mathematics.

Calculation of Areas and Volumes:

Archimedes used the method of exhaustion to calculate the area and volume of various shapes and solids. This method is a precursor to modern integral methods and is based on the idea of approximating a quantity by using increasingly smaller segments.

Method of Exhaustion:

Archimedes’ method of exhaustion involved dividing a shape into increasingly smaller parts to approximate the area or volume of that shape. An example of this method is the calculation of the area of a circle by inscribing polygons with more and more sides within the circle. As the number of sides increases, the inscribed polygon more closely approximates the circle, allowing for an increasingly accurate estimate of its area.

The Importance of Summation:

Archimedes understood that the key to calculating these quantities was the summation of many small parts. For example, to calculate the volume of a sphere, he approximated it using thin slices (cylindrical disks), the sum of which gives the volume of the sphere.

This process of summation is essentially the foundation of integral calculus, which was fully developed thousands of years later by mathematicians such as Newton and Leibniz. Integral calculus enables the calculation of the total area or volume of a shape through the cumulative approximation of infinitesimally small parts.

The Legacy of Archimedes:

Archimedes’ influence on calculations and the understanding of geometric shapes remains evident to this day. The use of the method of exhaustion and the realization that geometric shapes can be approached through infinitesimal processes were fundamental steps toward the development of mathematical analysis.

Archimedes also demonstrated that infinite processes and infinitesimals are not merely philosophical concepts but can be used to accurately solve practical mathematical problems. His techniques were so advanced that they were used for over two thousand years until they were further developed by the mathematicians of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment.

Conclusion:

Archimedes paved the way for the development of integral calculus through the method of exhaustion and the summation of infinitesimally small parts. His methodologies remain fundamental in mathematical education and the understanding of geometry and analysis, and his legacy continues to influence modern science and technology.

Calculus is one of the most important fields of mathematics, with key applications in the calculation of limits, derivatives, and integrals. One of the central topics in calculus is finding the length of a curve and using limit-based approximation, known as the limit approach. These methods laid the foundation for the development of mathematical analysis and have significant applications in many scientific and technological fields.

The Principle of the Limit Approach:

The limit approach is the process through which a problem is approximated using increasingly smaller segments. This idea is fundamental to understanding the length of a curve, calculating the area of a surface, or even estimating volumes. The concept is that as the segments used become infinitely small, the total sum of these segments approaches the exact value of the quantity being calculated.

Calculating the Length of a Curve:

One of the main applications of the limit approach in calculus is the calculation of the length of a curve. To calculate the length of a curve, we can approximate the curve with a series of straight line segments. As these segments become smaller and smaller, the total distance that approximates the entire curve becomes increasingly accurate.

Archimedes’ Contribution:

Archimedes, one of the greatest mathematicians of antiquity, made tremendous advances in using the limit approach to calculate areas and volumes. One of his most famous works is the approximation of the number pi using polygons inscribed and circumscribed in a circle. By using increasingly large polygons, Archimedes was able to approximate the number pi with remarkable accuracy.

Archimedes also applied the concept of calculus to the study of curves and areas, laying the foundation for the later development of mathematical analysis.

Calculus and Modern Mathematics:

The development of calculus by Archimedes and other ancient mathematicians is the foundation for modern mathematical analysis. These methods are widely used in many fields, such as engineering, physics, and technology, providing accurate and effective solutions for modeling and analyzing complex systems.

In conclusion, calculus and the use of limit approaches are central concepts in mathematics, allowing for the precise description and analysis of continuous phenomena found in nature and science. The legacy of ancient mathematicians, such as Archimedes, continues to influence modern thought and research, maintaining its importance in the mathematical and scientific communities.

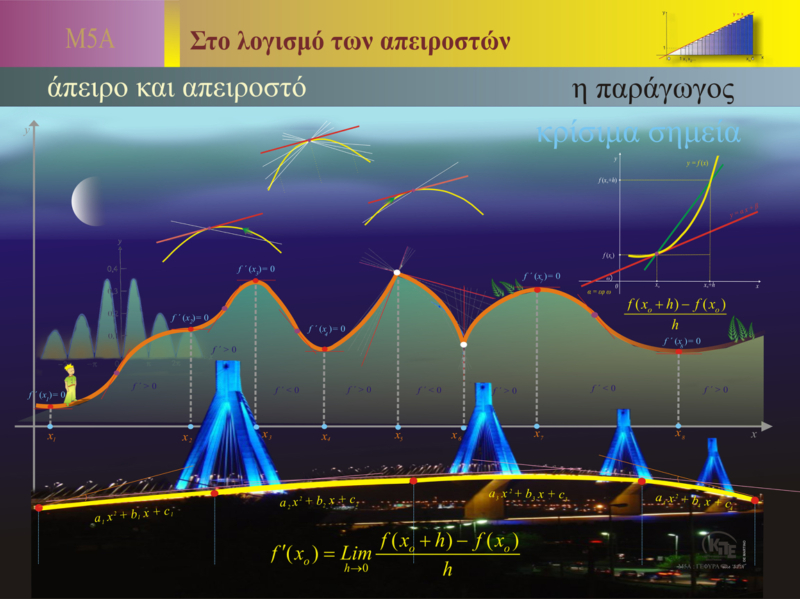

Calculus is a fundamental field of mathematics that deals with the concept of infinity and the infinitesimal. The derivative is one of the central concepts of calculus and is critically important for understanding the behavior of functions and solving problems involving change.

Derivative of a Function:

The derivative of a function at a point describes the rate of change of the function with respect to its independent variable. The derivative is given by the limit of the average slope of the function as the change in the variable approaches zero.

Critical Points and Maxima/Minima:

The critical points of a function are the points where the derivative of the function is zero or undefined. At these points, the function may have local maxima, minima, or inflection points. For example, if the derivative changes sign from positive to negative, the point is likely a local maximum, whereas if it changes from negative to positive, the point is likely a local minimum.

The study of critical points is important for finding the maximum and minimum values of a function, which is essential in many practical problems such as optimization and cost analysis.

Infinitesimal and Infinitely Large:

In calculus, the concepts of infinitesimal and infinitely large are fundamental. An infinitesimal is a quantity so small that it is nearly zero, but not exactly zero. These quantities are used to describe tiny changes in physical values, such as the velocity of an object at a specific point along its trajectory.

On the other hand, the infinitely large is a quantity so vast that it has no finite limit. Mathematicians use these two extremes to describe and understand the behavior of functions and systems that exhibit extreme values.

Applications of the Derivative:

The derivative has widespread applications in physics, engineering, economics, and other fields. For example, in kinematics, the derivative of position with respect to time gives velocity, while the derivative of velocity gives acceleration. In economics, the derivative can be used to find the rate of change in demand with respect to the price of a product.

Conclusion:

The derivative is one of the most powerful tools in calculus and enables the analysis of changes and variations across a wide range of applications. Understanding derivatives and the critical points of a function is essential for solving optimization problems and understanding the behavior of physical systems. The use of infinity and infinitesimals in calculus provides the necessary mathematical tools to address complex and dynamic real-world problems.

Calculus is a fundamental field of mathematics that deals with the concept of infinity and the infinitesimal. The derivative is one of the central concepts of calculus and is critically important for understanding the behavior of functions and solving problems involving change.

Derivative of a Function:

The derivative of a function at a point describes the rate of change of the function with respect to its independent variable. The derivative is given by the limit of the average slope of the function as the change in the variable approaches zero.

Critical Points and Maxima/Minima:

The critical points of a function are the points where the derivative of the function is zero or undefined. At these points, the function may have local maxima, minima, or inflection points. For example, if the derivative changes sign from positive to negative, the point is likely a local maximum, whereas if it changes from negative to positive, the point is likely a local minimum.

The study of critical points is important for finding the maximum and minimum values of a function, which is essential in many practical problems such as optimization and cost analysis.

Infinitesimal and Infinitely Large:

In calculus, the concepts of infinitesimal and infinitely large are fundamental. An infinitesimal is a quantity so small that it is nearly zero, but not exactly zero. These quantities are used to describe tiny changes in physical values, such as the velocity of an object at a specific point along its trajectory.

On the other hand, the infinitely large is a quantity so vast that it has no finite limit. Mathematicians use these two extremes to describe and understand the behavior of functions and systems that exhibit extreme values.

Applications of the Derivative:

The derivative has widespread applications in physics, engineering, economics, and other fields. For example, in kinematics, the derivative of position with respect to time gives velocity, while the derivative of velocity gives acceleration. In economics, the derivative can be used to find the rate of change in demand with respect to the price of a product.

Conclusion:

The derivative is one of the most powerful tools in calculus and enables the analysis of changes and variations across a wide range of applications. Understanding derivatives and the critical points of a function is essential for solving optimization problems and understanding the behavior of physical systems. The use of infinity and infinitesimals in calculus provides the necessary mathematical tools to address complex and dynamic real-world problems.

Calculus is one of the most powerful and fundamental tools in mathematics, with two main pillars: differential and integral analysis. Integration is the process of finding the area under a curve and is one of the central concepts of integral analysis.

The Concept of Integration:

Integration is closely related to the concept of limits and summation.

Riemann Integral:

Georg Friedrich Bernhard Riemann, one of the most important mathematicians of the 19th century, developed the concept of the Riemann integral, which forms the foundation of classical integration theory.

From Summation to Integration:

The transition from summation to integration is a central idea in mathematics. While summation is finite and involves a specific number of terms, integration refers to the process of taking the limit of an infinite sequence of sums as the segments become infinitesimally small. This process is crucial for accurately calculating areas, volumes, and other physical quantities.

Fundamental Theorem of Calculus:

The fundamental theorem of calculus connects differential analysis with integral analysis.

Applications of Integration:

Integration has widespread applications in many fields. In physics, it is used to calculate areas, volumes, work, and energy. In engineering, it is critical for analyzing structures and studying dynamic systems. In economics, integrals are used to model cumulative quantities such as total cost or total profit.

Conclusion:

Integration is a fundamental mechanism for understanding and analyzing continuous quantities. Through the concept of the integral, mathematicians and scientists can calculate areas, volumes, and other significant quantities with precision. The development of integral theory by mathematicians such as Riemann was crucial to the advancement of mathematics and science in general, providing the necessary tools for analyzing and understanding the physical world.

Take it differently (30 minutes)

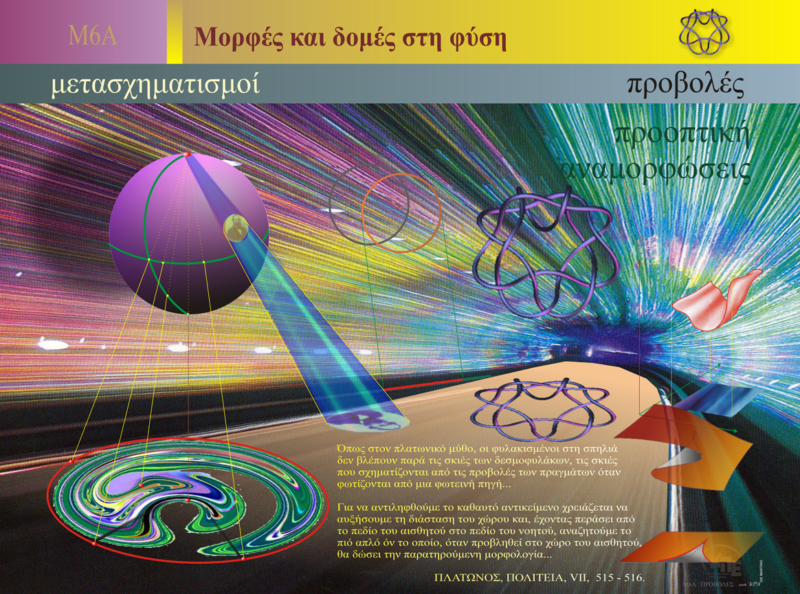

Transformation and projection are central concepts in geometry and mathematics, with applications across a wide range of fields including physics, engineering, art, and architecture. Transformations involve changes in the position, shape, or size of geometric figures, while projections refer to the process of representing three-dimensional objects in two dimensions.

Transformations

Transformations are mathematical processes that alter the position or shape of an object. Some of the most common types of transformations include:

– Translation: The movement of an object from one location to another without changing its shape or size.

– Rotation: Turning an object around a point or an axis.

– Reflection: Flipping an object across a line (in two dimensions) or a plane (in three dimensions).

– Dilation: Changing the size of an object while maintaining its shape.

Projections

Projections are methods used to create two-dimensional representations of three-dimensional objects. The most common types of projections include:

– Orthographic Projection: Used to create representations that preserve the true dimensions of an object. Each face of the object is projected onto a plane perpendicular to its surface.

– Perspective Projection: Used to create images that mimic the way the human eye perceives objects. Parallel lines in the actual object appear to converge at a vanishing point on the horizon in the drawing, creating a sense of depth.

Transformations and Forms in Nature

Nature offers many examples of transformations and deformations. From the growth of plants and animals to the patterns formed by fluid flow, transformations are present everywhere. For instance, ocean waves continuously transform as they approach the shore, and vortices in air and water create complex geometric patterns.

Projections in Art

In art, projections and deformations are used to create works that play with perspective and spatial perception. Renaissance artists, for example, developed the technique of perspective to add depth and realism to their paintings.

Applications in Engineering and Architecture

Transformations and projections are essential in the design and construction of buildings, bridges, and other structures. Engineers use mathematical methods to calculate transformative forces acting on an object, such as bending and deformation, while architects employ projections to create drawings that depict how a building will appear from various viewpoints.

Conclusion

Transformations and projections are foundational concepts in mathematics and science, with a wide range of applications extending from physics and engineering to art and architecture. By understanding these concepts, we can analyze and interpret the world around us, as well as design new structures and works of art that influence the way we perceive space and time.

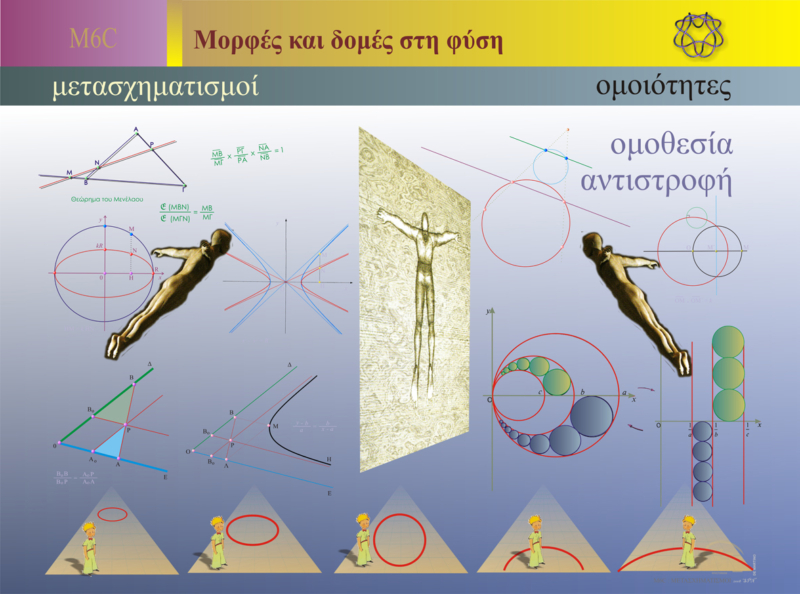

Fundamental Geometric Transformations

Similarity and inversion are fundamental geometric transformations that preserve the structure of a shape while changing its size or orientation. These transformations are central to the study of geometric relationships and have broad applications in mathematical analysis and physics.

Similarity (Dilation):

Similarity is a transformation that maintains the shape of an object while altering its size. In a similarity transformation, angles remain unchanged, while the distances between points are scaled by a constant ratio known as the similarity coefficient.

Dilation: Dilation is a specific type of similarity where all points of a shape are moved along lines that pass through a fixed point (the center of dilation), and the distances from the center are multiplied by a constant ratio. This ratio determines whether the shape will enlarge (when the ratio is greater than 1) or shrink (when the ratio is less than 1). Similarity is critical to understand geometry and is widely used in architecture, engineering, and physics, where scaled models of real objects often need to be studied.

Inversion:

Inversion is a geometric transformation that reverses the direction of points with respect to a circle. In this transformation, a point P outside the circle is mapped to a new point P′ inside the circle such that the product of the distances from the center of the circle remains constant.

Inverse Relationship: Inversion changes the orientation of a shape and can transform circular shapes into other circles or straight lines, depending on their position relative to the circle of inversion.

Inversion plays an important role in geometric analysis and transformation theory and has applications in optics and the study of symmetric systems.

Applications of Transformations:

Similarity and inversion transformations are critical for modeling and understanding symmetry in nature and geometry. Architects and designers use these transformations to create structures that are harmonious and aesthetically pleasing. In physics, such transformations help in understanding scale-related phenomena, such as fluid and gas dynamics.

Conclusion:

Similarity and inversion are foundational concepts in geometry that allow us to analyze the relationships between different geometric shapes and preserve their structure while changing their size or orientation. These concepts are useful both in theoretical studies and in practical applications, ranging from architecture and engineering to physics and mathematics.

Rouá mat (60 minutes)

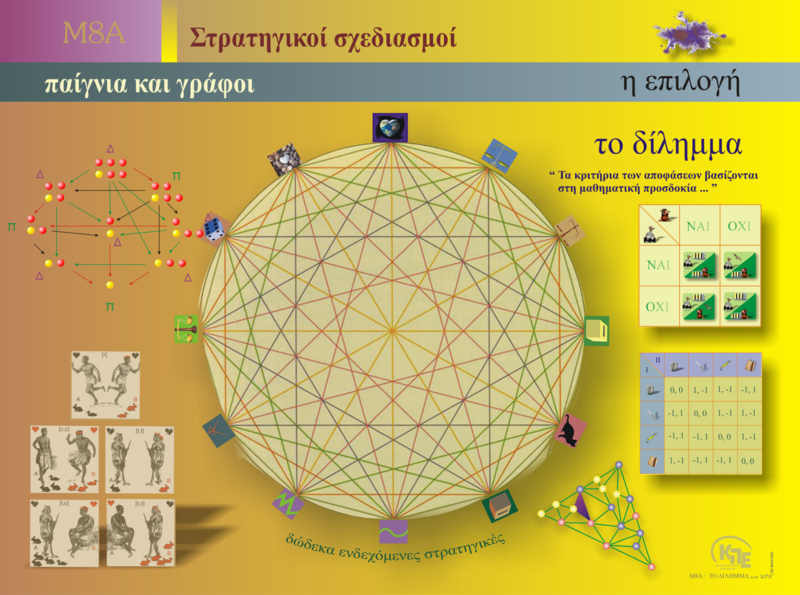

Game theory and strategic planning are branches of mathematics concerned with analyzing situations where outcomes depend on the decisions made by multiple individuals or ‘players’. In such contexts, each player seeks to maximize their benefit, taking into account the choices of others.

Game Theory:

Game theory emerged as a branch of mathematics and economic theory, focusing on modeling strategic interactions between rational decision-makers. Each game consists of a defined number of players, each choosing a strategy. The outcome of the game is determined by the combination of strategies chosen by all players.

Types of Games:

Zero-sum games: In these games, the total benefit gained by all players is zero. This means that one player’s gain is exactly equal to another’s loss. A classic example is chess, where one player’s victory results in the other’s defeat.

Non-zero-sum games: In these games, the overall outcome can either benefit or harm all players, depending on their strategies. Negotiations are an example, where cooperation can lead to mutual gain.

Classic Games:

The Prisoner’s Dilemma: A classic game theory problem demonstrating how uncertainty and lack of trust can lead to a less favorable outcome. Two prisoners must decide whether to betray each other or cooperate. Although cooperation yields the best collective outcome, fear of betrayal may lead both to betray, resulting in a worse scenario.

The Game of Chicken: In this game, two drivers head toward each other on a narrow road. The first to swerve to avoid a collision is considered the ‘chicken’ and loses. This game is often used to describe conflicts where neither side wants to back down.

Strategies and Graphs:

Strategies used by players in a game are often analyzed using mathematical tools such as graphs. Graphs can represent players’ strategic choices and their relationships. Through graphs, stable states of a game can be identified, known as Nash equilibria, where no player has an incentive to change their strategy unless others do as well.

Mathematical Expectation and Rational Decisions:

Mathematical expectation is a crucial tool in decision-making. By calculating the expected value of outcomes based on their probabilities, players can choose the strategy that maximizes expected return. This approach is essential in risk analysis and strategic decision-making.

Applications:

Economics: Game theory is used to understand competitive markets, pricing, and sales strategies.

Politics: It analyzes interactions between states, such as negotiations, alliances, and conflicts.

Psychology: It is used to study human behavior, strategic choices, and decision-making under pressure.

Biology: Applied to the study of evolution, cooperation, and competition among species.

Conclusion:

Game theory and strategic planning provide essential tools for understanding decision-making in complex, interactive environments. Through them, we can gain deeper insights into human behavior, improve negotiation outcomes, and develop strategies that lead to more desirable results, both personally and professionally.

Strategic analysis and game theory are essential for understanding and resolving conflict situations, where the decisions of each party influence the outcomes for all involved. These theories support the study of conflict dynamics and guide decision-making toward strategic advantage.

Game Theory and Strategic Analysis:

Game theory analyzes strategic choices made in settings where multiple ‘players’ or agents interact. Strategic analysis involves studying the decisions each player must make to achieve the best possible outcome, taking into account the potential decisions of others.

Nash Equilibrium:

One of the most important results in game theory is the concept of Nash equilibrium, introduced by mathematician John Nash. A situation is in Nash equilibrium when no player can improve their outcome by unilaterally changing their strategy. This equilibrium provides a stable solution in conflict scenarios where players have opposing interests.

Strategic Games and Conflict:

Strategic games represent situations in which players must select a strategy based on the potential choices of others. In these games, each player attempts to identify their optimal strategy by considering the possible strategies of their opponents.

Examples of Strategic Games: A typical example is the game of Battleship, where two parties must decide where to position their ships and where to strike. Strategy selection depends on how each player assesses the opponent’s moves.

Strategic Analysis in Military Strategy:

Strategic analysis has wide-ranging applications in military planning, where understanding conflict dynamics is critical for gaining a tactical advantage.

Submarine and Air Dominance: The strategic positioning of submarines and air forces is analyzed using game theory models that account for the interactions between forces and the goal of minimizing losses while maximizing advantage over the opponent.

Strategic Positions and Attacks: Choosing points of attack or defense is based on models that assess how each action may affect the overall outcome of a conflict. Strategic analysis helps identify critical points and inform decisions that minimize risk and maximize gain.

Applications in Various Fields:

Politics and International Relations: Strategic analysis is used to understand negotiations and diplomatic conflicts between states, where each side seeks the best possible agreement while considering others’ responses.

Business and Management: Business decisions are often based on strategic market and competitor analysis to secure an advantage over rivals.

Psychology and Human Relations: Understanding strategic interactions can help resolve conflicts and improve relationships by analyzing the motivations and goals of the involved parties.

Conclusion:

Strategic analysis is a powerful tool for understanding and predicting behavior in conflict and competitive scenarios. Through game theory and strategic analysis, mathematicians, analysts, and professionals can develop strategies that minimize risk and maximize benefit, regardless of the field of application.

Strategic Analysis in Games

Games, such as chess, are often used in game theory to understand how strategic decisions affect outcomes. Each move is critical, and players must anticipate the opponent’s response. They may choose to attack (conflict) or defend (alliance), each leading to different outcomes.

Conflict or Alliance

A central question in strategic analysis is whether players choose conflict or alliance:

– Conflict: Players act competitively, seeking to maximize personal gain at others’ expense. This can result in unstable outcomes.

– Alliance: Players cooperate toward a common goal. This often leads to more stable and efficient outcomes but requires trust and coordination.

Strategic Games and Graphs

Strategic analysis uses graphs to represent player options and potential outcomes. These graphs help identify optimal strategies and reveal relationships between players.

Variants like hexagonal chess are used to explore different dynamics and strategic implications among multiple players.

Decision-Making and Mathematics of Strategy

Decision-making is central to any strategic game. Players must assess probabilities, risks, and the likely actions of others. Mathematical tools such as game theory are used to calculate optimal strategies that maximize player benefit.

Conclusion

Strategic analysis and game theory provide tools for understanding decision-making in multi-agent situations with conflicting or aligned interests. Recognizing the dynamics of conflict and alliance and developing optimal strategies is key to success in competitive environments.

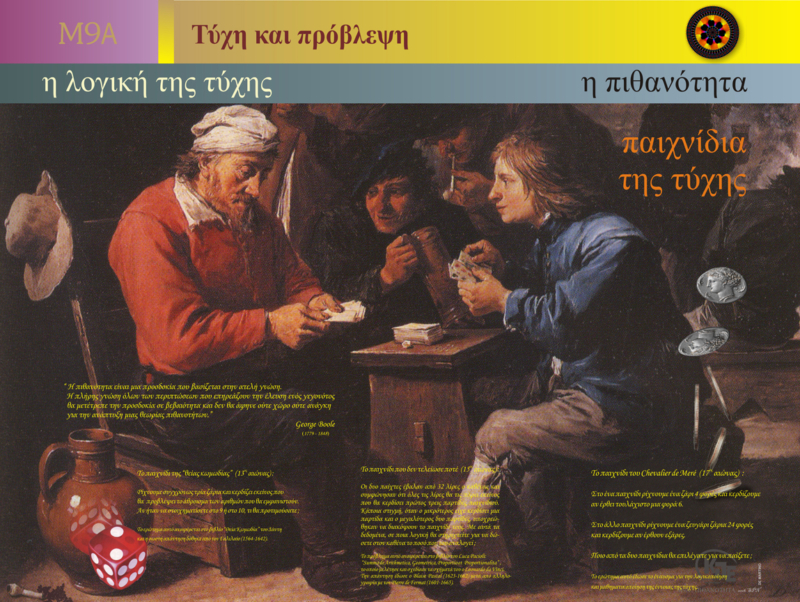

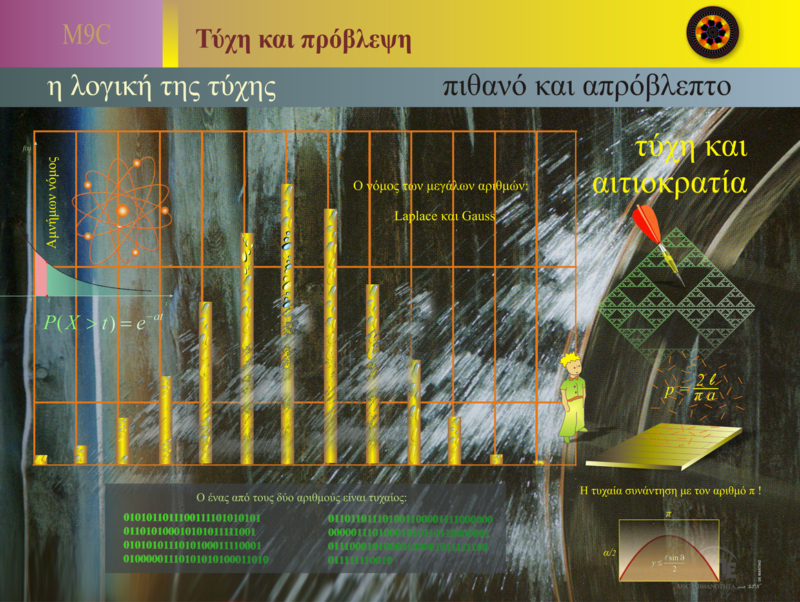

Probability Theory and the Logic of Chance

Probability theory and the logic of chance are fundamental pillars in mathematics and statistics, helping us understand and analyze phenomena involving uncertainty. The concepts of chance and prediction are essential for understanding games of chance, natural phenomena, and decision-making in uncertain situations.

The Logic of Chance:

Chance is often associated with events that cannot be predicted with certainty. However, through probability theory, we can determine the likelihood of various events, even if the specific outcomes remain unpredictable. The logic of chance was developed to model and quantify such phenomena.

Probability: The probability of an event is a number between 0 and 1 that expresses the likelihood of that event occurring. An event with probability 1 is certain, while an event with probability 0 is impossible.

Statistical Analysis: Statistics analyze data related to random events and allow us to make predictions about future events based on past data. Statistics are widely used in fields such as health sciences, economics, and sociology.

Games of Chance:

Games of chance, such as dice and poker, are based on probability and randomness. These games are often used as examples to explain concepts in probability.

Dice: In dice games, each face has an equal chance of appearing (1/6 for a standard six-sided die). While predicting the exact result of a dice roll is impossible, the probability of rolling a specific number can be calculated precisely.

Coin Toss: In a coin toss, there are two possible outcomes — heads or tails — each with a probability of 1/2, assuming the coin is fair and balanced.

Cards: In card games, the probability of drawing a specific card from a full deck of 52 cards can be calculated using basic principles of probability theory. For example, the probability of drawing an ace is 4/52 or 1/13.

Historical Development:

Probability theory began to develop in the 17th century when mathematicians such as Pierre de Fermat and Blaise Pascal tackled problems related to games of chance. Later contributions by mathematicians like Pierre-Simon Laplace expanded the theory and its applications to a wide range of fields.

Applications of Probability:

Probability theory has numerous applications in everyday life and science:

Insurance and Risk Assessment: Insurance companies use probability to calculate risk and determine premiums.

Economics: Economists use probability to analyze and forecast market trends and investment outcomes.

Health: Doctors and researchers use statistical probabilities to assess the effectiveness of treatments and predict disease progression.

Conclusion:

Probability theory enables us to approach uncertainty logically, providing the tools to quantify randomness and make informed decisions. In games of chance, understanding probability is essential for strategic decision-making, but its applications extend far beyond games, influencing all areas of human life.

Probability Distributions and the Logic of Randomness

Probability theory deals with the analysis and description of random phenomena, and probability distributions form a central part of this theory. By understanding probability distributions, we can describe how random events are spread and predict possible outcomes.

Law of Large Numbers and Distributions:

The Law of Large Numbers is one of the fundamental theorems in probability. According to this law, as the sample size increases, the average of results from repeated trials will approach the theoretical mean. This law explains why, for example, if you flip a coin many times, the proportion of heads and tails will approach 50%.

Binomial Distribution:

The binomial distribution is one of the most basic and important distributions in probability theory. It describes the number of successes in a series of independent and equally probable trials, such as the number of heads in 10 coin tosses.

Bernoulli Distribution:

The Bernoulli distribution is a special case of the binomial distribution involving only a single trial. It is the simplest probability distribution and is used to describe phenomena with two possible outcomes, such as a single coin toss.

Geometric and Hypergeometric Distributions:

Geometric Distribution: Describes the number of unsuccessful trials needed before the first success. For example, if you are trying to roll a 6 on a die, the geometric distribution describes how many attempts it takes to get the 6.

Hypergeometric Distribution: Used when trials are not independent. An example is drawing cards from a deck without replacement. The hypergeometric distribution describes the probability of drawing a specific number of successes (e.g., aces) from a limited sample.

The Bell Curve of the Normal Distribution:

The normal distribution, also known as the Gaussian distribution, is one of the most important in probability theory. It is described by the bell curve and is used to model many natural and social phenomena. This distribution is particularly significant because many random variables tend to be normally distributed when the sample size is large, due to the Central Limit Theorem.

Applications of Probability Distributions:

Statistical Analysis: Distributions are used to analyze data and make predictions in many fields, such as economics, health sciences, and engineering.

Insurance: Insurance companies use distributions to calculate risk and determine premium rates.

Games of Chance: In games of chance, probability distributions help understand the odds of winning and develop strategies to optimize gains.

Conclusion:

Understanding probability distributions is fundamental for analyzing random phenomena and quantifying uncertainty. Through distributions, we can describe how random events are spread and make predictions based on statistical models, with applications ranging from economics and science to everyday challenges.

Chance, Probability, and Causality in Mathematics and Statistics

Chance and probability are concepts that often appear to contrast with logic and determinism, yet in reality, they are closely connected through mathematics and statistics. Probability theory aims to quantify chance, predict the possible outcomes of random events, and understand unpredictable phenomena.

The Probable and the Unpredictable:

In everyday life, random events are often unpredictable, such as tossing a coin or selecting a random number. However, through probability theory, we can determine the likelihood of these events and understand their potential outcomes. This means that while individual events may be unpredictable, their collective behavior can be described with mathematical precision.

Law of Large Numbers:

The Law of Large Numbers states that as the number of repetitions of a random experiment increases, the average of the results tends to approach the theoretical expected value. This implies that if you flip a coin many times, the probability of heads and tails will tend toward 50%, even if the initial outcomes are skewed.

Normal Distribution and the Laplace-Gauss Law:

The normal distribution, or Gaussian curve, is one of the most important tools in probability theory. It describes how data are distributed around the mean in a large set of observations and forms the foundation for many statistical models. The Laplace-Gauss Law suggests that many physical and social variables follow a normal distribution, meaning they form a bell-shaped curve when plotted graphically.

Determinism and Random Numbers:

Determinism in physics and mathematics refers to the idea that every event has a cause. However, the existence of random numbers shows that there are phenomena which, although deterministic, appear random due to the complexity of their causes or our inability to know all the variables.